Home and History: Twentieth-Century Cuba in the Landscapes of Roger Toledo

Brett Robert

Ph.D Student, Department of History at the University of Pennsylvania

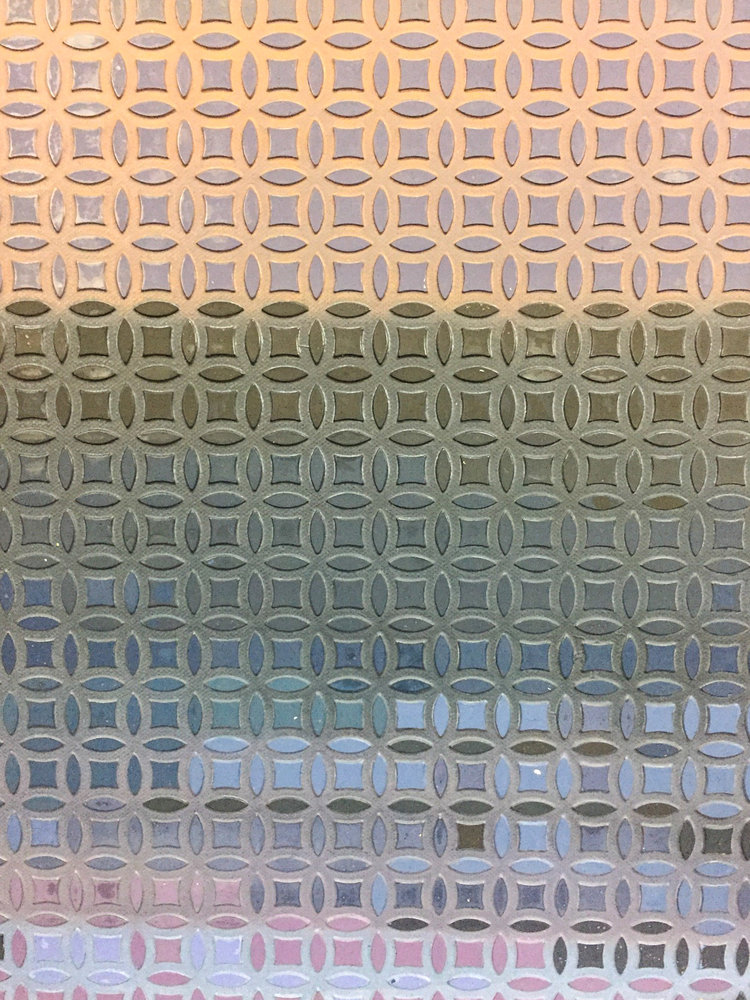

The landscapes of Roger Toledo’s “Soy Cuba” series represent meditations on the meaning of home in Cuban society through simultaneous portrayal of both national history and the intimate spaces in which daily life takes place. The viewer faces five Cuban landscapes painted on six one-meter by one-meter canvases joined together to create a large work two meters tall by three meters wide. One painting depicts clouds above Cuba, inspired by the view out of an airplane window, another shows a view from Pico Turquino at dawn, the highest mountain in the nation, another shows Ciénaga Zapata in the mid-afternoon, a swampy location North Americans probably know as the Bay of Pigs, another the view of a beach facing north at dusk, and the final painting reproduces an underwater landscape as might be seen by scuba divers off the coast of Havana.[1] The scale of the paintings gives them an immersive quality, drawing the viewer in, creating a sense of the vastness of the natural spaces they depict. The viewer is simultaneously prevented from full immersion, screened out of these spaces, by the superimposition of a secondary image on top of the scene. Using a mixture of acrylic paint and modeling paste, Toledo created a raised a secondary painted layer on top of the image that he refers to as the “texture.” This secondary layer is formed into a linked-circle pattern, accomplished by molding the texture with a metal sheet, that has the effect of slightly-abstracting the landscape behind it.

Figure 1: Amanecer en el Pico Turquino by Roger Toledo, 2019, 200 cm x 300 cm, artist’s studio, Havana, Cuba. Photo courtesy Roger Toledo.

Each landscape in the series is recognizable, and yet the experience is as if one is viewing it through a screen or fence that distorts and alters the view. At once the viewer is invited into and pushed away from the image. The tension between invitation and interdiction is paralleled by the tension created by the depiction of exterior spaces and allusion to interior spaces in the paintings. The linked-circle pattern is a common pattern from decorative arts and one that evokes the visual culture of Cuba’s built environment, particularly the tiles and fences found in Cuban homes. A third tension exists within the series, placing the perspective of the viewer in spaces associated with historical events implies the presence of society at large in the paintings, yet the visual field presented by the artist is devoid of both humans and man-made structures, except for the superimposed pattern. These three tensions, combined with the history of the locations depicted in the series, invite the viewer to confront the question of how the individual contextualizes home within a nation and its history.

This paper will examine exactly how the series poses this question by examining the three separate components used to pose it. The five paintings can be broken down into two groups. First is the trio of paintings contemplating Cuban lands, which I explore in the first section of this paper, “Landscapes.” The second group of paintings depict the sea and sky that serve, in a way, as borders for an island nation which is otherwise almost borderless.[2] These are discussed in the “Borders” section. The third section, “Patterns,” discusses both the presence of decorative patterns in the Cuban built environment, and Toledo’s encounter with the metal screens he used to create the texture while completing a residency in Minnesota. Finally, the conclusion analyzes how these three contexts merge in the works in service of meditations on home, nation, history, and the individual.

Landscapes

The locations of the three landscapes within Cuba’s earthly bounds depicted in the series all have historical significance in Revolutionary Cuba. While it is not necessary to engage deeply with the rich historiography of Cuba in the twentieth century to interpret the paintings, an understanding of what happened in the places depicted opens avenues of interpretation beyond the aesthetic. Toledo’s paintings are not brash or iconoclastic. The questions they pose, including the one examined herein, invite meditation and introspection, not debate or altercation.

The lack of humans in the paintings is one of the methods through which Toledo accomplishes this. Toledo asks his viewer to form a relationship with the image based on a contemplation of the aesthetic beauty of the twin visual fields and an intellectual interpretation of the history of the physical site depicted. This is accomplished by the choice not to paint human figures in the landscape, while at the same time showing spaces with important human histories and filtering them through the decorative pattern so closely associated with man-made interior spaces. Were the same visual field populated with human figures of any kind, the interpretation of the work would change and become substantially less subtle. The interpretation of any of these paintings would be drastically altered by the inclusion of batistianos, indigenous Taínos, or hacendados, as the interpretation would have to account for the politics of representing those groups and the personal relationship of the viewer to the faces and bodies depicted.[3]

On November 25, 1956 Fidel Castro, Raúl Castro, and Che Guevara landed the yacht Granma in the southeast of Cuba with a small band of guerrillas. Between then and the flight of their opponent in the revolutionary war, the hated former dictator Fulgencio Batista, from Cuba on January 1, 1959, Castro’s forces spent many months conducting guerrilla operations in the Sierra Maestra mountains. Pico Turquino is the highest peak not just in the Sierra Maestra, but in all of Cuba. At the top of Pico Turquino there is a bust of Cuban poet Jose Martí, who was also a late nineteenth-century hero of the war for independence from Spain. Pico Turquino is as close to a sacred site as the Cuban Revolution can have. For those seeking to understand Cuba from a certain perspective, to hike to its peak and gaze forth from this summit is to walk literally in the footsteps of Fidel and Che and to set your eyes upon the landscape where they fought as comrades in the revolutionary struggle.

Toledo depicts the view from this peak at dawn. There are no accidents in paintings that take months to produce and years to conceive.[4] When asked about the history of these landscapes, Toledo responded that "placing the viewer in specific sites is the only way to trigger the historical content.”[5] This response is representative of Toledo’s reluctance to interpret for viewers his paintings, preferring to trust the viewer’s ability to interpret the artwork, given the proper context. Most of the context of Amanecer en el Pico Turquino is present in the image and the title, but it is necessary to understand the importance of the Sierra Maestra during the Cuban Revolution the Sierra Maestra was a place where men who became the subject of legends suffered and fought to create a new Cuba. Discussing a series of ambushes by Batista’s forces, Che Guevara wrote that “the bitter experiences of these surprises and our arduous life in the mountains were tempering us as veterans.”[6] Within the context of Revolutionary Cuba, the Sierra Maestra are where the Revolution transformed from the dreams of a small committed core of revolutionary leaders into a realistic possibility to replace Batista’s government, a site that tempered not just the men campaigning there, but forged the Revolution as a viable political alternative. Likewise, in the heroic myths that surround the revolution, this is where suffering transformed the revolutionaries from city-dwelling college-educated professionals into hardened veterans of guerrilla war.

The Sierra Maestra was also a site of conflict in the Cuban War of Independence in the 1890s, often referred to in the United States only as part of the Spanish-American War. Toledo himself made the journey to Pico Turquino as a young man, at least partially inspired by his father’s advice to explore Cuba before attempting to explore the world.[7] After taking a series of trucks into the countryside, Toledo and a group of seven friends spent several days hiking along the Toa River and in the Sierra Maestra. “At night we were thinking about these mambises, when they were fighting against Spain, they were living in these mountains,” Toledo explained in an interview at his studio.[8] He described his own trip as difficult and physically exhausting, as his group had underestimated how sparsely populated that region has become in recent decades. Hunger, rain, and exhaustion beset Toledo and his companions as they made their trek, yet after a certain turning point had been crossed, their thoughts turned to the mambises, to history. “We were thinking, like, ‘what were they eating?’ ‘Do you think they were walking in this whole area?’ We were…very into this idea of ‘this is home.’”[9]

The Bay of Pigs invasion was a low point in the history of the United States, but it became a point of pride for Revolutionary Cuba. The failure of the CIA-backed invasion in April 1961 by right-wing Cuban exiles embarrassed the United States and pushed Fidel Castro and the Cuban government to closer ties with the Soviet Union. More than 1,000 troops of the exiles’ Brigada 2506 landed at Playa Girón, about 180 kilometers southeast of Havana on the island’s southern shore. While the exiles expected to be embraced by the Cuban people as liberators, they were instead treated as invaders and defeated within three days by the military. The trial of Brigada 2506’s leaders was broadcast nationwide, and clips of the trials went on to become some of the most familiar footage to many Cubans.[10]

Toledo depicts Ciénaga de Zapata in the middle of the day. This was a high point for the Revolution, not only had it liberated the nation, but it had defended itself against what it viewed as a former colonizer.[11] While the United States never formally annexed Cuba, the U.S. interfered repeatedly in Cuban politics beginning in the 1890s and continuing through the CIA support of Brigada 2506 and beyond. In 1898 the U.S. entered the war against Spain in what had been a Cuban war for independence, and when the dust settled and the treaties were signed Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines were no longer Spanish colonies, but became U.S. possessions. Unlike Puerto Rico, Cuba was allowed its independence, but the U.S. insertion of the Platt Amendment into Cuba’s 1901 constitution allowed it to intervene and occupy Cuba constituted a limitation of sovereignty that created a neocolonial relationship. Additionally, the U.S. Navy established a base at Guantánamo Bay that remains a source of tension between the nations.

In the U.S. the action of Brigada 2506 is remembered as “The Bay of Pigs Invasion,” but Cubans refer to the area as either Playa Girón, or more precisely to the swampy area where the invaders landed, Ciénaga Zapata. The area was rough, inhospitable, and lacking in economic opportunity when Batista fled in 1959. The successful repulsion of the invasion was at least partially creditable to the gains of the early Revolutionary society which had brought roads, education, new economic opportunity, and public safety to the area around Ciénaga Zapata.[12] In Toledo’s painting we see this sun-drenched highlight of the Revolutionary Cuban state, which not only defended its people, but was defended by its people in gratitude for the material improvements it had rapidly delivered to them. The choice of midday light for this moment, and its order in Toledo’s sequence, places it as both the midpoint around which the series pivots, but also its literally bright spot and highlight.[13]

Figure 2: Al Anochecer by Roger Toledo, 2019, 200 cm x 300 cm, artist’s studio, Havana, Cuba. Photo courtesy, Roger Toledo.

Sunset is represented in the series by the painting Al Anochecer/At Dusk which depicts the blue hour light fading to the left side of the frame as night falls across a beach facing north at Varadero.[14] Several moments of mass emigration from Cuba have occurred after the establishment of Castro’s Revolutionary state, including in the early 1960s centered around the northern coast near Varadero, the Mariel Boatlift, and during the Special Period in the 1990s.[15] The points of departure in each of these faced north. For those who left in clandestine attempts, a night time departure was ideal to attempt to evade the Cuban Coastguard. This view, the view of the waves gently breaking near the shore as the yellows and oranges of sunset give way to the purples and blues of dusk and night is a view much like the last view from Cuba experienced by generations of emigres. Toledo chose to paint this landscape at dusk as a reference to these emigrants’ last view from Cuba.[16] While conceptually Toledo lists this painting last of the three landlocked paintings in the series, he conceived of it first and it was one of the first of the five completed.[17]

The Special Period, and the memory of its dramatic poverty, shaped not only the last three decades of life in Cuba, but the course of Toledo’s life. After the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 the Cuban economy collapsed as trade networks and supply chains that were dependent on Soviet ties ceased to exist. The shelves in stores were emptied within months and Cubans faced a protracted, serious, economic crisis throughout the nineties, which motivated waves of mass-emigration throughout the 1990s. An extreme example of this emigration is the case of Elián González, who was just six years old in November 2000 when he left Cuba with his mother and ended up in Florida alone and became the subject of an international custody battle after his mother died during the crossing.[18] Because Toledo was born in 1986 the majority of his formative years took place during the Special Period.[19] His parents had to leave behind work as academic art historians to take up work decorating leather belts to sell as souvenirs to tourists.[20] Toledo was around ten years-old at the time and joined his parents in the work. While he remembers the work fondly as something he and his sister did together with their parents as a family, he acknowledges the trauma of the Special Period.[21] “Traumatized could be a good word for it,” he says in response to a question about the time, continuing to note that “I think it was harder for adults, especially if they had small kids or older relatives for whom they had to provide.”[22] Not only did the children of the Special Period grow up shaped by economic scarcity, but they were raised by parents preoccupied with survival and forced to make difficult and extreme choices. While Toledo’s parents’ choice to leave careers in academia perhaps affected his family less dramatically than did Elián González’ mother’s choice to flee Cuba on a doomed boat in the dead of night, the time left its marks on all those who lived through it.

Collectively, these three landscapes produce a narrative, a testimony, of the marks that Cuba and its history have left on Toledo to this point. The narrative is a very human story, of an independence movement whose dreams were almost fulfilled in 1898, the revolutionary war of the fifties that became a revolutionary state in the 1960s, and the limitations of national revolution within the context of an increasingly global political and economic landscape. The paintings tie the individual to these historical processes. Standing before them, we view these paintings of Cuban landscapes from the same perspective of an individual standing in those actual landscapes. The large scale of the works which stand taller than most humans, the emotive character of the colors which so clearly evoke the times of day chosen for each setting, and the photorealistic mimesis of Toledo’s work draw the viewer into the spaces. Standing before them the viewer might imagine they hear the song of the morning birds on Pico Turquino, feel the mid-day heat of the swamps, or smell the salty sea air of Varadero. Yet, even as the scale of the works and Toledo’s skill in mimicking the breathtaking splendor of Cuba’s environs invite viewers to immerse themselves in the works, the view is filtered by the pattern Toledo places in the field of vision, a point which will be explored later in this paper. Each of the landscapes is depicted at a time of day, morning, noon, and night, which suggests intentionality on Toledo’s part. It would be obvious to assume that the sunset suggests the end of the revolutionary Cuban state.

I suggest, instead, that these middle paintings of the series represent Toledo’s personal testimony of the trauma of the Special Period and emigration in his life, and that the viewer is invited to witness them. After years of interviewing Holocaust survivors psychiatrist Dori Laub, himself a Holocaust survivor, theorized that survivors must narrate their story before a witness in order to process their trauma.[23] Laub’s work alongside literary scholar Shosana Felman in their coauthored monograph Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Pyschoanalysis, and History expanded trauma theory, noting that art “bears witness to what we do not yet know of our lived historical relation to events of our times.”[24] In this sense, Toledo’s Soy Cuba series bears witness to the traumas of the Cuban Revolution. The mambises of Jose Martí’s generation and the barbudos of Castro’s generation faced hunger, battle, rain, and the challenge of enduring years in the rough terrain of the Sierra Maestras. Some of these traumas Toledo himself reenacted or experienced first-hand in his trek to Pico Turquino. The Cuban people faced the invasion and bombing, and many of the residents of the are around Ciénaga Zapata and Playa Girón saw combat personally when Brigada 2506 came in 1961, precipitating the blockade and embargo that led to close Cuban-Soviet relations for decades. The Special Period brought with it a long, slow trauma. Hunger and general lack of resources beset the Cuban people.

For those of Toledo’s generation, they not only had to adjust in childhood to a sudden and extreme poverty, but they also had to cope with the twin horrors of watching their fellow citizens take desperate flight while not knowing how or if this crisis would end. These paintings serve as Toledo’s personal testimony of the trauma of a generation of Cuban survivors who stayed. In some senses they were abandoned, abandoned by the Soviet Union, abandoned by the emigrants, abandoned by the international community who chose not to fight against crippling U.S. sanctions that the Cuban government still refers to as a blockade. Toledo’s paintings anchor, in that sense, an understanding of national home not only in the important national historical sites depicted as emblematic physical locations in space, but also in the historical times in which Toledo lived and learned about as a boy and continues to experience as a man.

The Borders

As an archipelago Cuba has only one relatively tiny land border, along the disputed fence-line of the United States Naval base at Guantánamo Bay. The true boundaries for Cuba, both in the imaginary and real senses are the sea and sky. While international law may recognize territorial waters and airspace rights, the reality is that they form limits beyond which humans require machinery to pass. While Toledo once stated, “it was very clear from the beginning, if you don’t like the Cuban Revolution, you don’t like this project, [then] just leave the country,” the truth is that while leaving was always an option very few have had the ability to leave and return freely.[25] The sea and sky are borders that require not just passports and visas to cross, but also access to economic and political resources beyond the reach of most Cubans. Additionally, for Toledo these two paintings depict sites tied to the most recent, and most personal, events implied by the series. Toledo’s position as an artist allowed him to earn enough income to access both the undersea and aerial perspectives. The increasing popularity of Cuban art in the new millennium has allowed artists financial success not only greater than that available to many non-artists in Cuba, but which allows them to live more comfortably in Cuba than many of them could hope to live in New York or Paris.[26]

Figure 3: Roger Toledo, Aterrizando, 2019, 200 cm x 300 cm, artist’s studio, Havana, Cuba.

Although Toledo himself cannot recall whether the reference photograph he used in composing Aterrizando was taken out the window of a plane while returning to when leaving Cuba, he chose to title the painting with the Spanish word for landing.[27] Significantly, he listed this as the first in the series when asked for the titles of the works.[28] The fact that this “skyscape” is both first in the series and features a title that suggests an arrival in Cuba, is quite significant, particularly when considering the narrative arc of the circadian cycle depicted in the middle three paintings. Were the skyscape titled something like “saliendo,” “leaving,” or “huyendo,” “fleeing,” it would be difficult to interpret the narrative arc of the series as anything but a narrative about the end of the Cuban Revolutionary state. Instead, Toledo begins the series with his viewers arriving in Cuba, beginning from above.

Toledo lists the seascape of Hacia el Canto Beril/Towards Canto Beril as the final painting in the series, suggesting an ending point that is simultaneously tranquil and disorienting. Toledo’s personal encounter with the underwater environment stems from his own experiences scuba diving off the coast of Cuba. The accessibility of scuba diving in Cuba is driven by the rise in tourism after the Special Period, and in the case of Toledo personally, by the rising art market, also a post-Special Period development. Toledo describes feeling both tranquility and an acute awareness that he did not belong underwater. So peaceful was the underwater experience for him, that when having difficulty sleeping he remarked that he will sometimes picture himself sitting on the ocean floor, breathing through the respirator, until he is able to sleep.[29] Closing the series with a painting that depicts an environment the artist finds comforting suggests that the diurnal cycle depicted in the landlocked paintings in the series is a device not to suggest ending or failure, but rather transition towards the resolution depicted in the tranquility of Hacia el Canto Beril.

The border paintings mean that the cycle of sunrise, noon, and sunset shown in Amanecer en el Pico Turquino, Ciénaga de Zapata, and Al Anochecer marks not a linear narrative, but rather one iteration of a cycle. The series begins and ends not with sites included and selected primarily for their historical connections, but with locations relevant more to the artist’s life than to the larger history of the nation. The locations in Aterrizando and Hacia el Canto Beril are tied to Toledo’s mobility and economic success as an artist more than the national history. They mark the boundaries of Cuba, but not its end, nor the end of the Revolution. They are simply markers that stand in for the days preceding and succeeding the day depicted. Without skyscape and seascape, the orientation of the Soy Cuba shifts almost entirely away from the individual perspective and biography of their creator and towards the story of the nation. Their inclusion contextualizes the national story within the individual perspective. Toledo’s personal experiences as a privileged observer able to soar above and dive below Cuba become the bookends, the frame, and the boundary of the series, just as the sea and sky bound the nation.

The Pattern

Figure 4: :Close-up of Amanecer en el Pico Turquino. Photo courtesy of Heather Moqtaderi.

To discuss the exterior landscapes depicted in Toledo’s Soy Cuba series without discussing the pattern superimposed upon them, a pattern so reminiscent of the visual culture of the interior built environment of Cuba, is to miss quite literally half the picture. When viewed up close, the precision of the pattern is impressive, and the complexity of the technique to create these works becomes clear. When viewed from several meters away from the paintings, the effect of the pattern on the viewer’s experience of viewing the work is unavoidable. While the landscape, seascape, or skyscape remains recognizable, the pattern alters the aesthetic. The result could be described as a slight abstraction, pixelation, or even distortion of the mimetic quality of the painting.[30] From a visual, technical, and aesthetic standpoint, the effect is stunning and immediately remarkable. The viewer cannot have a relation with the landscape depicted without interpreting it through the filtering effect of the pattern.

The superimposition of this pattern, so reminiscent of the quotidian intimate spaces of Cuban life, onto the images of sites of Cuban history and the boundaries of Cuba, suggests a meditation on home. Not just the individual home, but the national home. Home not simply as the casa or hogar, the house or domicile, but the the imagined national community to which Cubans belong.[33] Toledo uses this device to simultaneously depict three aspects of Cuba: the physical landscape, the recent political history of human society there, and the home life.

Figure 5: A vitrale window from the Museum of Decorative Arts in Havana featuring the same pattern used in Toledo's Soy Cuba series. Photo courtesy Luiza Franca.

Figure 6: Close-up of the tile floor in Pedro Oliva’s studio in Pinar del Río. Photo courtesy Luiza Franca.

Figure 7: A fence in an artist’s studio in Pinar del Río, Cuba, featuring the same linked circle pattern used in Toledo's Soy Cuba series. Photo courtesy Brett Robert.

Conclusion

The Soy Cuba series captivates the attention of viewers with its powerful aesthetic statement and style, the mastery of craft in its execution, and the unique visual juxtaposition of an abstract pattern superimposed over a mimetic image. What is perhaps most masterful about the series is that this attention is rewarded and sustained by the rich cultural, personal, and historical references embedded in the series. The tension between invitation into the landscape, by the mimetic quality of the landscapes, and interdiction from total immersion, by the abstract layer distorting the image, serves not to prevent the viewer from interpreting the works, but rather to engage the viewer emotionally through the visual. Deeper interpretations made possible by familiarity with the cultural context unlock further categories of analysis and reveal another layer of tension between the exterior spaces represented and the interior spaces evoked. Understanding the history of the landscapes represented reveals the tension present between the history of human events that imbues the geographical spaces represented with additional meaning, and the painting before the viewer which shows a natural landscape devoid of human presence. The skyscape and seascape in the series introduce bind the topic, shaping it, limiting it to Cuba, but also framing this iteration of the diurnal cycle, suggesting that the narrative told in three parts be understood not as an ending or a failure.

The series stands as the testimony of Roger Toledo, a Cuban of the twentieth and twenty-century. A man whose home must be understood as a particular time, place, and culture. A witness to its history, traumatized, perhaps, by the uncertainties of history and the privations of material struggle during the Special Period. A man who stayed. An artist. Just as the mountains, the swamp, and the beach were witnesses to history, so was he. He offers them as testimony, so that viewers may bear witness to his trauma, to his history. Toledo offers them also as a challenge to the viewer, a question. What is home?

Notes

[1] Roger Toledo, Aterrizando/Landing, 2019, 200 cm x 300 cm, artist’s studio, Havana, Cuba.

Roger Toledo, Amanecer en el Pico Turquino/Dawn at Pico Turquino, 2019, 200 cm x 300 cm, artist’s studio, Havana, Cuba.

Roger Toledo, Ciénaga de Zapata, 2019, 200 cm x 300 cm, artist’s studio, Havana, Cuba.

Roger Toledo, Al Anochecer/At Dusk, 2019, 200 cm x 300 cm, artist’s studio, Havana, Cuba.

Roger Toledo, Hacia el Canto del Beril/Towards Canto Beril, 2019, 200 cm x 300 cm, artist’s studio, Havana, Cuba.

[2] The “almost” in this sentence refers, of course, to the land border at Guantánamo Bay where the United States of America maintains a military base on land it claims.

[3] Batistiano is a term for the supporters of the Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista who was deposed by the Cuban Revolution in the late 1950s. The Taíno were the indigenous inhabitants of many of the greater and lesser Antilles before the arrival of Europeans. Hacendado is a term for a wealthy proprietor of a large colonial estate, many of which included plantations, mines, or other means of income generation.

[4] For an in-depth discussion of the process involved in creating Toledo’s pieces see Francesca Bolfo “Working Title”

[5] Roger Toledo, email to Ramey Mize, November 13, 2018.

[6] Che Guevara, Reminiscences of the Revolutionary War in Cuba Reader: History, Culture, Politics, Aviva Chomsky, Barry Carr, Pamela Maria Smorkaloff (North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2003), 319.

[7] Toledo, email to Ramey Mize, November 13, 2018.

[8] Mambises here refers to the soldiers who fought for Cuba’s independence from Spain in the 1890s. The United States eventually intervened in this war and in the treaty at its conclusion in 1898 the United States ended up with control over Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Cuba. Subsequent conflicts between the Revolutionary Cuban state and the United States are related to the colonial relationship with the United States that was set up as a result of this war.

Roger Toledo, interview, October 8, 2018, Havana, Cuba.

[9] Toledo, Interview, October 8, 2018, Havana Cuba.

[10] See for example the use of the clips in Memorias del Subdesarollo, directed by Tomas Gutiérrez Alea (Havana, Cuba: Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos, 1968), digital video, https://itunes.apple.com/us/movie/memories-of-underdevelopment/id1415261773.

[11] While the United States never formally annexed Cuba, its insertion of the Platt Amendment’s demands into Cuba’s 1901 constitution allowed it to intervene and occupy Cuba constituted a limitation of sovereignty that created a neocolonial relationship .

[12] For a brief discussion of these improvements and the invasion see: Margaret Randall, “Women in the Swamps” in Cuba Reader: History, Culture, Politics, Aviva Chomsky, Barry Carr, Pamela Maria Smorkaloff (North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2003), pp. 364-369.

[13] Roger Toledo, email to the author, December 9, 2018.

[14] Roger Toledo, email to author, December 9, 2018.

[15] Toledo, interviewed by Robert, et al., October 8, 2018, Havana, Cuba.

[16] Toledo, interviewed by Robert, et al., October 8, 2018, Havana, Cuba.

[17] Toledo, email to Ramey Mize, November 13, 2018.

[18]The case made nightly news in the US and elsewhere at the time, for a recap of the initial events see: Evan Thomas, “Raid and Reunion,” Newsweek, April 30, 2000, https://www.newsweek.com/raid-and-reunion-157465.

[19] Toledo, email to Ramey Mize, November 13, 2018.

[20] Toledo, interview, Havana, October 8, 2018.

Roger Toledo, lecture at University of Pennsylvania, September 20, 2018.

[21] Toledo, interview, Havana, October 8, 2018.

[22] Toledo, email to author, December 9, 2018.

[23] Laub, Dori, “An Event Without a Witness: Truth, Testimony, and Survival,” in Shoshana Felman and Dori Laub, Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Pyschoanalysis, and History. New York: Routledge, 1992, pp. 75-92.

[24] Felman, Shoshana and Laub, Dori, Testimony: Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Pyschoanalysis, and History. New York: Routledge, 1992, pp. xx.

[25] Toledo, interviewed by Robert, et. al, October 8, 2018, Havana, Cuba.

[26] Ibid.

Toledo credited the financial opportunities available to him as an artist living in Cuba as one of the main reasons he has stayed even as many of his friends have left.

[27] Toledo, interviewed by Robert, et. al., October 8, 2018, Havana, Cuba.

[28] Toledo, email to Ramey Mize, November 13, 2018.

[29] Toledo, email to author, December 9, 2018.

[30] Toledo dislikes the use of the term “pixelation” in reference to these paintings, but the grid-like structure of the pattern produces an effect that many modern viewers find similar to the pixelation seen in digital images.

He noted his distaste for the term on multiple occasions, including personal conversations with the author and: Toledo, lecture at University of Pennsylvania, September 20, 2018.

[31] Toledo, lecture at University of Pennsylvania, September 20, 2018.

Toledo, email to author, December 9, 2018.

[32] Toledo, lecture at University of Pennsylvania, September 20, 2018.

For further discussion of the technique and preparatory works, see: (links to papers by colleagues)

[33] See Benedict Anderson’s seminal work on nationalism for an in-depth discussion of the concept of a nationa as an imagined community: Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (New York: Verson, 1983).