History on the Horizon in Roger Toledo Bueno’s Soy Cuba Series

Ramey Mize (doctoral student, History of Art)

“Before you meet the world, you have to meet Cuba.”

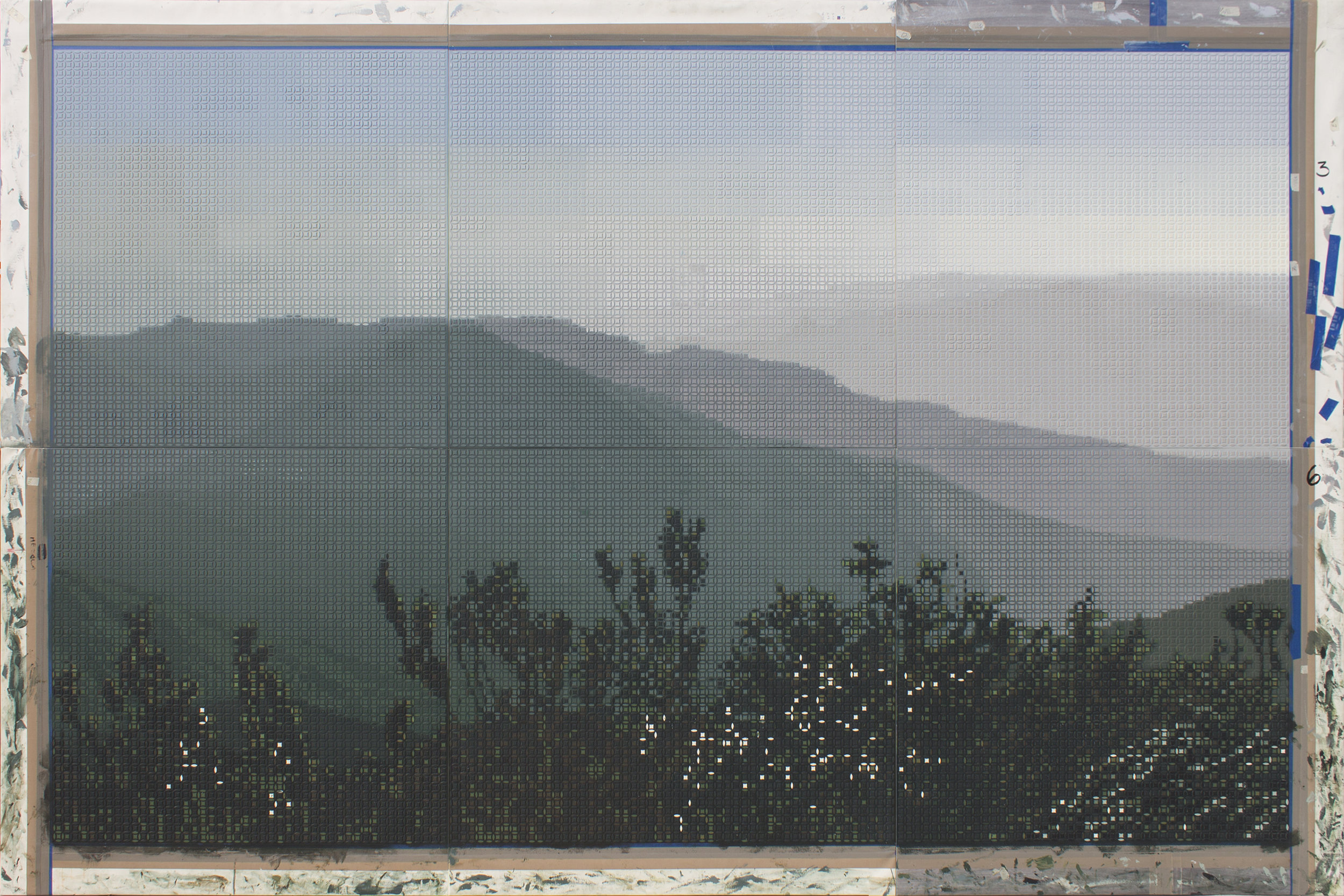

A view of the mogotes in Viñales Valley, a karstic depression located in the Sierra de los Órganos mountain range. Photograph by the author.

This advice, given to Roger Toledo Bueno by his father, did not go unheard. [1] Indeed, the Soy Cuba/I am Cuba series may be seen as a remarkable outcome of the artist’s ardent response to this counsel, a virtual window into the travels he undertook throughout the country following their conversation. Spanning approximately 40,000 square miles, Cuba constitutes the largest, most topographically and naturally diverse archipelago in the Caribbean Sea, and Toledo’s excursions were complicated and challenging as a result. [2] The island’s dynamic environs encompass the lush, soaring peaks of the Sierra Maestra mountain range, the seemingly endless combinations of coves and capes along vast, white ribbons of coastline, the teeming wetlands of the Zapata Swamp, and the otherworldly mogotes (limestone cliffs) of Viñales Valley. [3]

Over the last decade, Toledo has wended his way through these natural landmarks with assortments of friends and family members, experiencing them in all their vivid, verdant immediacy. The five scenes of Soy Cuba are similarly wide-ranging, each a testament to the probing character of Toledo’s peregrinations: an undulating cloudscape in Aterrizando (Landing), the view from a mountaintop in Amanecer en el Pico Turquino (Sunrise at Pico Turquino), the sunken scenery of Ciénaga de Zapata (Zapata Swamp), a crepuscular marine from Havana’s north shore in Al Anochecer (At Dusk), and finally, the murky fathoms of the sea in Hacia el Canto del Beril (Toward’s Beril’s Edge).

Together, the Soy Cuba paintings perform a visual reenactment of Toledo’s own visceral meeting with the Cuban landscape, and a major part of the work’s significance is in the very act of bringing viewers and vistas face to face. Key to this “encounter effect” is the artist’s investment in the horizon as a through-line, or a connective and orienting device. The horizon lines across all five expansive works remain fixed, hovering at the same height in each of the scenes pictured. Because the history of the horizon line as a compositional device in the genre of landscape painting is long, rich, and laden with meaning, it is important for us to situate Toledo’s work in relation to this lineage, considering the ways in which various painters, photographers, and writers—from Cuba and across the Americas—have previously instrumentalized the horizon in representations of landscape for political, national, and aesthetic ends. Through the contextualization of the horizon, it will become clear that Toledo’s Soy Cuba series offers an innovative rendition of this pictorial precedent, one that bespeaks mobility, immersion, and futurity, rather than mastery, minimization, and distance. The spatial span that Toledo’s paintings traverse is telling in this respect, and the following sub-sections—“Climbing,” “Diving,” and the conclusion, “Flying”—are titled accordingly, as gestures to the artist’s own movements and their evocation in these works. By moving in this way, we are able to unearth the horizon’s role as a potent protagonist within the cultural construct of landscape, both in Cuba’s history and present.

Part I: Climbing

Around the mid-nineteenth century, artists began to shape the general contours of landscape painting as a formal subject in Cuba, spurred in large part by Romanticism, a literary and artistic movement that stressed the role of landscape in national identity formation. [4] Art historian Narciso Menocal pinpoints the writer José María Heredia (1803–1839) as responsible for innovating the “Lyrical” strand of Cuban Romanticism, a mode evinced in his iconic poem, “Oda al Niágara" of 1824. [5] Heredia, along with many Euro-American writers and artists, endeavored to articulate his feelings in the face of Niagara’s furious falls, a reaction incited by his yearning for “the extraordinary and the sublime.” [6] The “terrifying violence” of the “plunging torrents” is tormenting as opposed to stirring, however, and the anguished poet finds himself asking, “Why don’t I see, encircling your immense chasm, the palm trees, ah! those delicious palm trees that on the plains of my beloved Cuba come to life blessed by the sun’s smile, and flourish; and in the waft of ocean breezes sway under a sky of spotless blue?” [7] An exile in the United States at the time he penned this verse, Heredia invokes Cuba’s indigenous flora and atmosphere while in the throes of his homesickness, preferring the salt-tinged air and sunshine of his country of origin to this thunderous North American cataract. [8] This poem crystallized, for the first time in literature and subsequently in painting, the island’s environment as a salient metaphor for Cuban selfhood. [9]

Though the sublime proportions of landscape were intimidating and undesirable for Heredia, this was by no means indicative of other Cuban artists’ predilections. Federico Fernández Cavada (1831–1871) for instance, instilled his work with approximations of this late-eighteenth-century aesthetic category, first defined by the Irish statesman and philosopher Edmund Burke (1729‒1797) in 1757 and later popularized in nineteenth-century artistic circles in the United States by painters associated with the Hudson River School. [10] In Río San Juan, Trinidad (1865), Cavada renders the San Juan River, set against the towering backdrop of the Escambray Mountains, in minute and formidable detail. [11]

Federico Fernández Cavada (1831–1871), Río San Juan, Trinidad (San Juan River, Trinidad), 1865, Oil on canvas, National Museum of the Fine Arts of Cuba, Havana.

Cavada, having served as a soldier in the Union Army during the U.S. Civil War (1861‒1865), developed an intimate familiarity with the prominent tropes of Hudson River School paintings; as such, his work bears stylistic and compositional resonance with representations by related artists like Thomas Cole (1801–1848) and his protégé, Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900). [12] The high horizon line of Cavada’s peaks, so lofty that the central summit is swathed in clouds, serves to emphasize the landscape’s inimitable scope, a fact that is even further underscored by the diminutive scale of the human figures visible in the foreground. Narciso Menocal has identified a compelling similarity between Cavada’s Río San Juan, Trinidad and Church’s Heart of the Andes (1859) in their convergence of intimate particulars with mountainous sublimity. [13]

Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), Heart of the Andes, 1859, Oil on canvas, 5 feet and six inches by 9 feet and 11 inches, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The diminished stature of humanity in these respective paintings is integral to their meaning. According to Daniela Bleichmar’s characterization of Latin American landscapes within Church’s output, the human actors appear “almost incidental, tiny blips against the spectacular grandeur of nature.” [14] During the 1850s, Church made two journeys to Ecuador and Colombia in search of new subject matter, inspired by the German naturalist-explorer Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) who had himself voyaged through the region from 1799 to 1804. [15] The aesthetic program that Church employs so insistently in Heart of the Andes may be understood within a more general pictorial rhetoric of possession particular to Euro-American landscape painting of the period. As art historian Jennifer Raab points out, the artist’s choice to render his signature as a carved incision across the tree at the lower left of the composition is a tell-tale sign of this acquisitive attitude, “a version of ‘I was here’ as well as ‘This is mine.’” [16] Bleichmar has also explored the newfound access enjoyed by traveler-artists and naturalists to Latin America by the mid-1820s, a development enabled through wide-scale, successful independence efforts against previous Spanish and Portuguese colonial regimes. [17] This unprecedented exposure eventually fueled a perceptual mode that premised dominance and exploitation in representations of the region, one that Bleichmar asserts “can be understood as belonging to an ‘imperial picturesque.’” [18] To be sure, this “imperial picturesque” portrayed by traveler-artists in Latin America is not so far afield from the compositional machinations of what art historian Albert Boime has dubbed the “magisterial gaze.” [19]

The “magisterial gaze,” according to Boime, is a “commanding view” that defines “the perspective of the American on the heights searching for new worlds to conquer.” [20] Critical to the conveyance of this ideological message is the “systematic projection of unlimited horizons,” a pictorial strategy which serves to envision such a “desire for dominance” as not only possible, but divinely ordained. [21] Thomas Cole’s View of the Round-Top in the Caskill Mountains, Sunny Morning on the Hudson (1827) is paradigmatic of this syndrome. The vaporous clouds that feather the looming pinnacles recall those that cloak the mountains in Cavada’s Río San Juan. In Cole’s canvas, however, the view is reversed—the spectator no longer peers upwards in aspirational awe, but rather from above with covetous authority and in full sight of the distant sun-soaked valley. [22]

Thomas Cole (1801–1848), View of the Round-Top in the Catskill Mountains, Sunny Morning on the Hudson, 1827, Oil on panel, 18 5/8 x 25 3/8 inches (47.31 x 64.45 cm), Gift of Martha C. Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 47.1200.

This brief sketch of some of the visual strategies and political ideologies at play in early, pan-American landscape painting is helpful in teasing out the larger stakes of Toledo’s own rendition of the genre’s conceits in the Soy Cuba series. Toledo has expressed the importance of dimensional dynamics in his practice, going so far as to claim the intricacies of “space and spatial relationships” as central among his pictorial concerns. [23] This preoccupation indicates the profundity of the artist’s choice to position Cuba’s landscapes as places to approach, with the individual and the environment on equal terms. Amanecer en el Pico Turquino makes this compositional leveling effort especially plain. Here, the mountains consolidate into a frieze-like band, extending across the entirety of the painting’s lower half. The peaks, seen from the highest point of the Sierra Maestra mountain range, neither dwarf nor elevate the viewer—they do not rear upwards in disorienting resplendence, as in Cavada’s Río San Juan or Church’s Andes, and they betray no hint of gleaming, endless terrain beyond, as in Cole’s View of the Round-Top. Toledo’s mountains face their viewers, on equal terms and without any undue pageantry or bombast. Through this emphatic departure from a proprietary perspective, the artist brings the landscape into a clear field of vision without presumptions of ownership, awe, and extraction. Here, the “encounter effect” is recognizable as such, in an astonishing repetition of the exhortation expressed by the artist’s father. In other words, it is as if Toledo employs this painting, and the Soy Cuba series at large, to make the same proposal to viewers: “Meet Cuba.” The constant and level horizon line is crucial to this end, as well as Toledo’s decision to free the horizon of its burden of yielding an impression of three-dimensionality and deep space.

Roger Toledo Bueno, Amanecer en el Pico Turquino (Sunrise at Pico Turquino), 2018, Acrylic on canvas, 78 3/4 x 118 inches (200 x 300 cm); Comprised by six panels of 39 3/8 x 39 3/8 inches (100 x 100 cm).

The rich, insurrectionary history of this particular site in Cuba is also key to the painting’s meaning. Pico Turquino is located in the easternmost province of Cuba historically referred to as “Oriente,” a rugged area characterized by the dramatic terrain of the Sierra Maestra range. [24] The distance and relative remoteness of this province made it an ideal setting for insurgent activities and guerrilla warfare, and the Sierra Maestra has been the location of choice for many of Cuba’s notable revolutionary efforts over the last 150 years. [25] These include Cuba’s struggle against Spanish colonial rule in the Ten Years’ War (1868‒1878) and the Cuban War of Independence (1895‒1898), as well as the Cuban Revolution led by Fidel Castro (1926‒2016) and his 26th of July Movement against Fulgencio Batista (1952‒1959) in 1959. [26] The poet and political theorist José Martí (1853‒1895) is widely regarded as foremost among Cuba’s iconic revolutionary figures, having died fighting against the Spanish royalist army in the Battle of Dos Ríos in 1895, not far from Pico Turquino. [27] In 1953, Celia Sánchez Manduley (1920‒1980) placed a bust of Martí, carved by Jilma Madera (1915‒2000), at the peak’s zenith to commemorate the centenary of the writer’s birth; two months later, Manduley would also lead Fidel Castro’s forces into these same mountains to recover and rebuild after their failed attack on the Moncada barracks in Santiago. [28] Literary historian Peter Hulme has explored the considerable impact of geography in the early development of the Cuban Revolution and subsequently revolutionary culture, invoking the following comment made by Castro on the emotional resonance of Pico Turquino as powerful evidence: “If I could follow my heart, the place where my deepest feelings would lead me to live would be El Pico Turquino. Because against the fortress of the tyranny we established the fortress of our invincible mountains.” [29] With this historical context, the view pictured in Toledo’s painting suddenly sharpens; this is not an arbitrary or a neutral outlook, but one that is densely layered with national narratives and mythologies, a veritable “peak” of revolutionary experience.

In the company of friends who had also grown up in Oriente, Toledo summited Pico Turquino during his studies at the Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA) in Havana. [30] The arduous, 6,746-foot trek taken by the group echoed that of the revolutionaries before them and served to elucidate Toledo’s awareness of the site’s confluence of historical and individual experience. “At a point, it’s not about making the image.” he reflected when asked about the relationship of his working photographs to the final paintings. “It’s about many memories and histories coming together.” [31] The Soy Cuba series therefore offers a much deeper encounter with Cuba, a meeting with both the country’s physical topography and the reverberations of its history. In effect, Pico Turquino looks out across a horizon of both space and time, coalescing into a single, bright panorama that activates personal and collective registers of meaning in equal measure. [32]

It is important to clarify that Toledo portrays this scene solely in an effort to bring Cuba into the realm of the visible, without any underlying message or pointed agenda. The bust of Martí placed by Sanchez is, after all, not included in this composition, nor is the detritus of the revolutionary occupation. The political valence of the locale remains exclusively within the title’s textual domain, leaving the pictorial plane open to resonate with viewers in dynamic ways. Toledo provides more than one prospect: an embodied sight from a particular pinnacle and a vision of Cuba itself. In other words, there is space for anyone, regardless of national origin, to step in front of this overlook, peer across its expanse and experience its scenery on their own terms—and yet, not entirely out of context. This is again part of the broader “aesthetics of encounter,” a visualization that carries significant import in Cuba’s case because the Cuban archipelago is a place that is remarkably hard to see, a condition that Toledo at once recognizes and transcends with this body of work.

Part II: Diving

Roger Toledo Bueno, Al Anochecer (At Dusk), 2018, Acrylic on canvas, 78 3/4 x 118 inches (200 x 300 cm); Comprised by six panels of 39 3/8 x 39 3/8 inches (100 x 100 cm). [Placeholder photograph]

A transition now from the precipitous altitude of Pico Turquino down to sea level in Toledo’s ocean paintings will reveal the somewhat different connotations of the horizon when considered against Cuba’s insular environment. Al Anochecer is a mesmeric marine seen from Havana’s north shore, bedecked with the fugitive, opalescent gradations of color—lavender, cornflower, cerulean, eggplant, navy, apricot, and gold, among others—that play across both water and sky at twilight. [33] The ocean’s massive volume below the horizon line fills the same passage of canvas occupied previously by mountains in Amanecer en el Pico Turquino. Intriguingly, the central, rolling wave in forms another kind of monumental crest across the foreground. In this scene, the unique, technical method by which Toledo renders the painting’s surface intersects with and reinforces the series’ conceptual implications. Toledo constructs his images from acrylic paint thickened with modeling paste. [34] With the aid of metal sheets comprised of consistent, geometric cut-outs, he carefully applies individual mixtures of pigments, building up the canvas into a web of regular, low-relief shapes that he has dubbed the “pattern” or “texture” of the picture. [35] This complex additive process requires multiple applications of carefully mixed paint, followed by surface sanding for an even finish. The result of this additive process is a tantalizingly haptic veneer, one that embeds within itself the palpable traces of the metal sheet’s screen-like structure. Toledo’s fabrication of an open horizon out of something close to its antithesis—the stiff, cage-like enclosure of a grille—is striking. In Al Anochecer, as well as in the other works of Soy Cuba, Toledo presents a raised and perforated horizon line that is both destination and limit, a contradictory conjunction that is evocative of Cuba’s island condition. [36]

The nature of island life’s uneasy simultaneity between restriction and possibility is a prominent trope with both art history and Caribbean studies. [37] Art historian Nathalie Bondil, for example, has pointed out the sea’s function as “both boundless horizon and a boundary,” asserting its place as a central motif in Cuban art: “While island dwellers are always aware of the vastness of the world, they also always have a sense of the physical limits of their own territory, surrounded on all sides by water.” [38] Curator Natania Remba has also appraised the “ambivalent” regard that contemporary Cuban artists hold for their water-locked state, portraying the ocean as both “isolating” and “liberating” in turn. [39] Remba eloquently surmises: “Located somewhere between these two poles of representation is a more complete picture of how motifs and symbols of confinement and freedom function in Cuba’s visual vocabulary.” [40] The poet Virgilio Piñera (1912‒1979) offered similarly divergent takes on the subject. In the poem “La isla en peso” (“The Whole Island”), first published in 1943, Piñera opens with the following verses:

“La maldita circunstancia del agua por todas partes

me obliga a sentarme en la mesa del café.

Si no pensara que el agua me rodea como un cáncer

hubiera podido dormir a pierna suelta.”

“The curse of being completely surrounded by water

condemns me to this café table.

If I didn’t think that water encircled me like a cancer

I’d sleep in peace.” [41]

Here, the circumscription of the ocean takes on pervasive, pathological proportions; Piñera strikes a more hopeful tone, however, in the following excerpt from a later poem written in 1979, simply titled “Isla” (“Island”):

“Se me ha anunciado que mañana,

a las siete y seis minutos de la tarde,

me convertiré en una isla,

isla como suelen ser las islas.

[…]

Después, tendido como suelen hacer las islas,

miraré fijamente al horizonte,

veré salir el sol, la luna,

y lejos ya de la inquietud,

diré muy bajito:

¿así que era verdad?”

“It was announced to me that tomorrow

at six after seven in the evening

I would become an island,

an island like any other.

[…]

Afterwards, as islands do

I will stare at the horizon,

see the sun and moon emerge,

and far now from anxiety

whisper softly

‘did that really happen?’” [42]

In this imaginative, human-archipelago metamorphosis, Piñera positions horizon-gazing as an island’s special lot, and in this way recognizes the visual proscriptions that Toledo engages in Al Anochecer: islanders also experience the magnetic pull of the distance, eyes locked on the vague beyond, just “as islands do.”

Armando García Menocal (1863‒1942), Nighttime at the Bay, c. 1930, Oil on canvas.

Armando García Menocal (1863‒1942) was among the earliest artists to depict Cuba’s insular status in painting, and his canvas Nighttime at the Bay (c. 1930) embodies this irresistible optical urge to search for the beyond. [43] A lone man at the lower left crouches precariously atop a single rock, his chin resting on crossed forearms. He directs his gaze across a rippling cove, almost afire with vivid white highlights from the moon’s evanescence. It is as if we adopt this figure’s stance when we step in front of Toledo’s Al Anochecer, which suddenly permits us to see through islander eyes. To put it another way, Toledo’s composition instates the visuality of Cuba’s island condition for all who catch sight of it.

These fluctuating evocations of distance, isolation, and constraint expressed by Menocal and Piñera during the 1930s and 70s were immeasurably compounded in the 1990s following the onset of what has come to be called the “Período Especial” or the “Special Period” in Cuba. [44] The Cuban economy, largely dependent on financial aid from the Soviet Union, took a major blow following its supporter’s collapse and the ensuing enforcement of an even stricter U.S. embargo. [45] In 1990, the “Special Period in Time of Peace” was officially declared by the Cuban Government and, as art historian Stephanie Schwartz succinctly puts it, “scarcity reigned.” [46] Rachel Weiss, an arts administration and public policy scholar, describes a major consequence of this crisis as the dissolution of the Revolution’s “epic horizon. . . buried as aspiration in the struggle to survive.” [47] Like their friends and neighbors, Toledo’s family experienced the full force of the rampant economic devastation. I argue that the harrowing memory of the Special Period makes itself known in the artist’s Soy Cuba series by virtue of the screen element, and that this painterly partition constitutes an internal remnant or indication of the geo-political blockade that Cubans experienced during this time. [48]

The photographic series Aguas Baldías (Water Wastelands) (1992‒94) by Manuel Piña (b. 1958) affords an illuminating comparison on this point. Monochrome and melancholic, these works were produced at the start of the Special Period and takes Havana’s prominent sea wall, the Malecòn, as their subject. In two images (Untitled, 1992 and a second Untitled, 1992), the craggy, stained surface of the concrete swallows up almost the entire focus, the upper edge forming a horizon line that is exceedingly claustrophobic.

In another picture from the series, we see the artist mid-leap from the Malecòn, his body arrested against another imposing wall—of water. Piña described the open horizon at this time as a “trauma of space,” and here it is an undoubtedly unnerving and imposing band of blank flatness. [49] The apparent interchangeability between the sea wall and the sea renders the horizon line obdurate, and Piña’s photographic study emphasizes each as an implacable obstacle, with the sea, like the wall itself, dark and impassive. Through this series, Piña signals the cruel irony of the waterway’s transformation from a fluid thoroughfare to an emphatic enclosure under these socio-political circumstances. [50]

Manuel Piña, Aguas Baldías, 1992

Roger Toledo Bueno, Hacia el Canto Del Beril (Toward’s Beril’s Edge), 2018, Acrylic on canvas, 78 3/4 x 118 inches (200 x 300 cm); Comprised by six panels of 39 3/8 x 39 3/8 inches (100 x 100 cm). [Placeholder photograph]

The embedded, screen-like “texture” in Toledo’s Al Anochecer recalls the synergistic affiliation between the ocean and the Malecòn in Aguas Baldías, but only to a point. Though the screen is there, a constitutive agent of the picture, it still coheres into a legible image that is larger than the sum of its disparate parts. Furthermore, while Piña’s wall of water is an impenetrable mass providing no means of escape or release, Toledo presents a roiling sea that is fluid and pervious, evidenced by the dive below the surface that is effected in the next work in the Soy Cuba series, Hacia el Canto del Beril. This underwater view brings with it a horizon almost oxymoronic by virtue of its submarine setting, signified only through a vague haze that seems to quiver and drift. The soft blurriness of the sponges, rocks, and coral, coupled with the saturated blue hues, emits a sense of calm, quiet suspension. The ocean floor stretches forward, the site of so much life, but the association between these fathoms and a watery grave is difficult to ignore.

Indeed, it is important to remember that it was also during the 1990s that la crisis de los balseros (the rafter crisis) unfolded, a single aspect of a broader sequence of mass exoduses from Cuba to the United States that have occurred over the past half-century and continue today. [51] These “continuous waves of passage,” as Natania Remba calls them, necessarily involve perilous stakes, risks that many migrants have been willing to take. [52] The symbolic “dive” of Hacia el Canto del Beril thus allows for a profound experience of the otherwise life-threatening deep, and as such, projects an emancipatory alternative to this historical precedent. With this work, Toledo side-steps the traditionally ambivalent oceanic account, and instead offers it as a place of pause and reflection. [53] Layers of history hover within Toledo’s painting, and within the entirety of Soy Cuba, as integral as the horizon line. These layers are light, without the weight the past so often carries, and enrich rather than overload their vantages.

Conclusion: Flying

Roger Toledo Bueno, Aterrizando (Landing), 2018, Acrylic on canvas, 78 3/4 x 118 inches (200 x 300 cm); Comprised by six panels of 39 3/8 x 39 3/8 inches (100 x 100 cm). [Placeholder photograph.]

Recalling the astonishing plunge of Hacia el Canto del Beril, Toledo surges skywards in Aterrizando. The act of air travel carries with it particular connotations for Cubans, for whom mobility and travel is more of a rare privilege than a given option. [54] Yet, the artist staves off easy presumptions regarding the meaning of this work through his choice of title—significantly, he confirms that this flight is not an outbound, but rather it is a return. In Aterrizando, Toledo not only commemorates his commitment to “meet Cuba,” but also amplifies it, meeting Cuba again after returning from elsewhere. Tomás Sanchez (b. 1948), the most celebrated Cuban landscape painter of the late-twentieth century, portrays a similar aerial scene in Nubes y sombras de nubes (Clouds and Cloud Shadows), though his clouds are insubstantial wisps and tufts of air, levitating unassumingly over an indistinct green earth. [55] The air in Aterrizando, however, is dense, the clouds forming a vast, undulating plain seemingly substantial enough to cross on foot. Toledo has painted a vapor that is akin to solid ground. A wall of air in the sky, the clouds become another barrier that Cubans must breach to leave or access their island home.

Tomás Sanchez (b. 1948), Nubes y sombras de nubes (Clouds and Shadows of Clouds), 1987, Acrylic on canvas.

Movement is the premise of both Aterrizando and the Soy Cuba series as a whole. Building on this idea, Toledo has expressly articulated his intention for the works in Soy Cuba to “place viewers in different levels of physical existence.” [56] The series enacts a virtual mobility for its audiences in this way, carrying them to radical heights and depths in a powerful performance of actions not easily undertaken. Finally, it is also clear that the motion inherent to Soy Cuba conjures the forward-moving, continuous passage of history and time. History, as we have seen, is not a foreclosed narrative for Toledo; rather, it paves the way for an opening, a potentiality, as expansive as the very horizon. Past and present meet in these paintings, clarifying the possibilities for a future where Cuba is not only seen, but also sees itself.

Author Bio: Ramey Mize is a doctoral student in Art History at the University of Pennsylvania. From Atlanta, Georgia, she holds a BA in Art History from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and her MA from the Courtauld Institute of Art in London. The majority of her research and publications to date examine the intersection of nineteenth-century visual culture, war, and landscape across Europe and the Americas. Previously, she worked as the Anne Lunder Leland Curatorial Fellow at the Colby College Museum of Art in Waterville, Maine; most recently, she co-curated the exhibition "The World is Following Its People”: Indigenous Art and Arctic Ecology at the University of Delaware's Old College Gallery. Since 2016, she has served as a managing curator of the Incubation Series, a student-run curatorial collective at Penn.

Endnotes

1 From a conversation with the author on June 11, 2018 in Havana, Cuba.

2 Cuba is considered a part of the Greater Antilles, a grouping of larger Caribbean islands including Haiti, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, and the Cayman Islands. See Natania Remba, Surrounded by Water: Expressions of Freedom and Isolation in Contemporary Cuban Art (Boston: Boston University Art Gallery, 2008), 17. According to Daniel Velasco, the “markedly changeable climatic conditions in Cuba” and “the relative isolation of the island have encouraged the development of . . . (m)ore than 3,200 species,” making Cuba home to “by far the largest number of native plants of any island or island group.” Velasco goes on to detail the significance of this biological diversity in Cuba’s unique “acoustic ecology”; see “Island Landscape: Following in Humboldt’s Footsteps through the Acoustic Spaces of the Tropics,” Leonardo Music Journal 10 (2000): 21–24.

3 For a detailed treatment of Cuban geography and the larger social, natural, and cultural valences of the country’s landscape, see Joseph L. Scarpaci and Armando H. Portela, Cuban Landscapes: Heritage, Memory, and Place (New York: Guilford Press, 2009).

4 Ernesto Cardet Villegas, “Discovering the Cuban Landscape,” in Cuba: Art and History from 1868 to Today, ed. Nathalie Bondil (Montreal: The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 2008), 50; Narciso G. Menocal, “An Overriding Passion: The Quest for a National Identity in Painting,” The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts 22 (1996): 191. According to Menocal, “Cuban themes began to evolve when Romanticism initiated a search for a national identity, first in literature and then in painting.”

5 Menocal, “An Overriding Passion,” 191. For an exploration of the role of Niagara as a literary landmark in Heredia’s oeuvre as well as the poet’s special role in the dissemination of the Romanticist movement in Cuba, see Adam Glover, “Crisis and Exile: On José María Heredia’s Romanticism,” Decimonónica: Journal of Nineteenth-Century Hispanic Cultural Production 10:1 (Winter 2013): 78–96.

6 For the full poem, see José María Heredia, Torrente Prodigioso: A Cuban Poet at Niagara Falls, ed. and trans. Keith Ellis (Toronto: Lugus Publications, 1997).

7 Ibid.

8 Jeremy Adamson chronicles the North American engagement with Niagara Falls as a creative motif in Niagara: Two Centuries of Changing Attitudes, 1697–1901 (Washington, DC: Corcoran Gallery of Art, 1985).

9 Menocal, 191.

10 Burke delineated his definitions of “the sublime” versus “the beautiful” in his influential Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful, first published in 1757.

11 The Escambray Mountains, or Sierra del Escambray, are located in the south-central region of Cuba, encompassing the provinces of Sancti Spíritus, Cienfuegos, and Villa Clara.

12 Menocal, 193.

13 Ibid.

14 Daniela Bleichmar, Visual Voyages: Images of Latin American Nature from Columbus to Darwin (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017), 198.

15 Jennifer Raab, “‘Precisely these objects’: Frederic Church and the Culture of Detail,” Art Bulletin 95 (December 2013): 578. Church owned all five volumes of Humboldt’s Cosmos, along with numerous other important texts from the scientist’s published output.

16 Ibid., 579.

17 Bleichmar, Visual Voyages, 158.

18 Ibid. For a compelling consideration of the perceived “heroic” status of the traveler-artist, see Chapter 7, “The Primal Vision: Expeditions,” of Barbara Novak’s Nature and Culture: American Landscape and Painting, 1825–1875 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 119–134. Katherine Manthorne has also written an expansive treatise on North American traveler-artists in this region in Tropical Renaissance: North American Artists Exploring Latin America, 1839–1879 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1989).

19 For a book-length treatment of this concept, see Albert Boime, The Magisterial Gaze: Manifest Destiny and American Landscape Painting, c. 1830–1865 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, 1991).

20 Ibid., 22.

21 Ibid., 26. Angela Miller describes nineteenth-century nationalist aesthetics in the U.S. as “anticipatory and prophetic,” deriving this description from popular rhetoric of the period; see Empire of the Eye: Landscape Representation and American Cultural Politics, 1825-1875 (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1993), 15.

22 Boime defines an upward-focused view, one that is exemplified in Cavada’s painting, as the “reverential gaze,” a perspective that “signified the striving of vision toward a celestial goal in the heavens, starting from a wide, panoramic base. . . . That is precisely the inverse of the American gaze,” 22.

23 From a conversation with the author on June 11, 2018 in Havana, Cuba.

24 Cuban provinces were first established in 1879 by Spanish colonial decree. Oriente, which was referred to as “Santiago de Cuba” before 1905, was a historical region that now contains the present-day provinces of Las Tunas, Granma, Holguín, Santiago de Cuba, and Guantánamo. Oriente was divided in 1976 under Cuban Law Number 1304 as part of an administrative re-adjustment. For more on the socio-cultural history of this area, see Peter Hulme, Cuba’s Wild East: A Literary Geography of Oriente (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2001).

25 Ibid., 2.

26 For a history of the warfare during Cuba’s colonial period, see Ada Ferrer, Insurgent Cuba: Race, Nation, and Revolution, 1868‒1898 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999). Marifeli Pérez-Stable provides an in-depth chronicle of the political and social conditions that gave rise to the 1959 Revolution during Cuba’s neo-colonial period; see The Cuban Revolution: Origins, Course, and Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999). Sujatha Fernandes traces the intersection of art and revolutionary culture in Cuba Represent!: Cuban Arts, State Power, and the Making of New Revolutionary Cultures (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006).

27 For a biography of José Martí, see Alfred J. López, José Martí: A Revolutionary Life (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014).

28 Peter Hulme, “Message in a Bottle: The Geography of the Cuban Revolutionary Struggle,” in Literature, Geography, Translation: Studies in World Writing, ed. Cecilia Alvstad, Stefan Helgesson, and David Watson (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011), 231. Celia Sánchez Manduley was a member of the Twenty-Sixth of July Movement and the first female combatant in the revolutionary army; she later assumed the role of secretary of the Council of State as well as personal secretary and companion to Fidel Castro. Tiffany A. Thomas-Woodard has analyzed her contribution to and legacy in Cuban revolutionary politics and memory in the article “‘Towards the Gates of Eternity’: Celia Sánchez Manduley and the Creation of Cuba’s New Woman,” Cuban Studies 34 (2003): 154‒180.

29 Peter Hulme, “Message in a Bottle: The Geography of the Cuban Revolutionary Struggle,” in Literature, Geography, Translation: Studies in World Writing, ed. Cecilia Alvstad, Stefan Helgesson, and David Watson (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011), 231. Celia Sánchez Manduley was a member of the Twenty-Sixth of July Movement and the first female combatant in the revolutionary army; she later assumed the role of secretary of the Council of State as well as personal secretary and companion to Fidel Castro. Tiffany A. Thomas-Woodard has analyzed her contribution to and legacy in Cuban revolutionary politics and memory in the article “‘Towards the Gates of Eternity’: Celia Sánchez Manduley and the Creation of Cuba’s New Woman,” Cuban Studies 34 (2003): 154‒180.

30 From a conversation with the author on October 8, 2018 in Havana, Cuba.

31 Isabelle Lynch explores the ways in which Toledo’s work enacts a spatialization of time; see her essay “Island Time,” also on this website.

32 Color is an integral element of Toledo’s artistic practice and technical process; see “Vision and Color” by Francesca Bolfo for an in-depth exploration of this aspect.

33 Toledo sources these metal sheets from Home Depot, having first discovered them there while in residency in Minneapolis during the summer of 2015.

34 From a conversation with the artist on October 8, 2018 in Havana, Cuba.

35 I derive this term “island condition” from Corina Matamoros Tuma’s essay, “The Island Burden: Insularity and Singularity,” included in Cuba: Art and History from 1868 to Today, ed. Nathalie Bondil (Montreal: The Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, 2008). Tuma posits that “The condition of being an island, an emigrant’s trauma, and the conflicts of nationality appear everywhere in [Cuban] art,” 336.

36 See, for instance, Tobias Ostrander, On the Horizon: Contemporary Cuban Art from the Jorge M. Pérez Collection (Miami: Pérez Art Museum, 2016) and Godfrey Baldacchino, “Islands as Novelty Sites,” The Geographical Review 97 (2007): 165‒174.

37 Nathalie Bondil in ibid., 18.

38 Remba, “Surrounded by Water,” 11.

39 Ibid.

40 Virgilio Piñera, La Isla En Peso (The Whole Island), trans. Mark Weiss (Exeter, United Kingdom: Shearman Books Ltd, 2010), 12.

41 Ibid., 13.

42 Mark Weiss, ed. and trans., The Whole Island: Six Decades of Cuban Poetry, A Bilingual Anthology (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009), 105.

43 Another early painter of these coastal scenes was Leopoldo Romañach (1862‒1951). Villegas, “Discovering the Cuban Landscape,” 52 ; Gary R. Libby, Cuba: A History in Art (Gainesville: University of Florida, 2015), 21. For more on Menocal and Romañach, see Juan A. Martínez, Paul Niell, and Segundo J. Fernandez, Cuban Art in the 20th Century: Cultural Identity and the International Avant-Garde (Tallahassee: Florida State University, 2016), 26‒29.

44 Ariana Hernández-Reguant provides a thorough overview of the development and challenges of this period; see her edited volume Cuba in the Special Period: Culture and Ideology in the 1990s (New York: Palsgrave Macmillan, 2009). See also C. Paponnet-Cantat, “Cultural Dimension of Cuban Painting and Influence of the Special Period on Contemporary Cuban Art Work,” The International Journal of the Humanities 9 (2012): 69‒80.

45 Aviva Chomsky, Barry Carr, and Pamela Maria Smorkaloff, eds., The Cuba Reader: History, Culture, Politics (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), 595. For an analysis of the impact of United States policy on Cuban art, see Chapter 33, “The Manifested Destinies of Chicano, Puerto Rican, and Cuban Artists in the United States” in Shifra Goldman’s Dimensions of the Americas: Art and Social Change in Latin America and the United States (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994).

46 Stephanie Schwartz and Manuel Piña, “Chronicles: A Conversation with Manuel Piña,” Third Text 23:3 (May 2011): 281.

47 Rachel Weiss, To and from Utopia in the New Cuban Art (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 160.

48 From a conversation with the artist on October 8, 2018 in Havana, Cuba.

49 “Manuel Piña, From the Series Aguas Baldias (Water Wastelands),” The Museum of Fine Arts Houston, accessed November 1, 2018, https://www.mfah.org/art/detail/27123.

50 Nelson Ysla Herrera has characterized Aguas Baldías as a photographic inquiry into questions of “freedom and enclosure” during this moment in Cuba’s history. See his article “Photography in Caribbean Art,” Art News 33 (August‒October 1999): 89. Rachel Weiss has defined the series in similar terms, interpreting these images as all “frames enclosing the horizon,” To and from Utopia in the New Cuban Art, 180.

51 Elizabeth Campisi has compiled a series of interviews from migrants who participated in this mass departure; see Escape to Miami: An Oral History of the Cuban Rafter Crisis (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

52 Remba ties the rafter crisis to those migrations that have preceded it, including Cubans seeking to escape Spain’s colonial oppression in the nineteenth century, in the wake of the Cuban Revolution in 1959, and in the 1980s during the Mariel boat lift. See Surrounded by Water, 14.

53 It is interesting to note that Toledo himself is a passionate scuba diver and has invoked the bottom of the sea as a place of meditative respite and describing this underwater experience as capable of enabling “a happy reconciliation with the environment.” 57 From a conversation with the artist on October 8, 2018 in Havana, Cuba.

54 From a conversation with the artist on October 8, 2018 in Havana, Cuba.

55 Veerle Poupeye has commented on the surreal, metaphysical quality of Tomás Sánchez’s oeuvre in his survey Caribbean Art (London: Thames and Hudson, 1998), 148.

56 From a conversation with the author on October 7, 2018, in Havana, Cuba.

![Roger Toledo Bueno, Al Anochecer (At Dusk), 2018, Acrylic on canvas, 78 3/4 x 118 inches (200 x 300 cm); Comprised by six panels of 39 3/8 x 39 3/8 inches (100 x 100 cm). [Placeholder photograph]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5be9dc194611a0faf5d5d873/1544647710514-VV2G81X4MWN029BI9LQ0/Al+Anochecer.jpg)

![Roger Toledo Bueno, Hacia el Canto Del Beril (Toward’s Beril’s Edge), 2018, Acrylic on canvas, 78 3/4 x 118 inches (200 x 300 cm); Comprised by six panels of 39 3/8 x 39 3/8 inches (100 x 100 cm). [Placeholder photograph]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5be9dc194611a0faf5d5d873/1544648291129-XKHWJRETGBDMB463BCN9/Toledo_Canto+del+Beril.jpg)

![Roger Toledo Bueno, Aterrizando (Landing), 2018, Acrylic on canvas, 78 3/4 x 118 inches (200 x 300 cm); Comprised by six panels of 39 3/8 x 39 3/8 inches (100 x 100 cm). [Placeholder photograph.]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5be9dc194611a0faf5d5d873/1544648374748-QTDFTEVRO3OF23YMRSZX/Toldeo_Aterrizando.jpg)