Island Time: Temporality and History in Roger Toledo’s Soy Cuba/I am Cuba Series

Isabelle Lynch (doctoral student, History of Art)

The tally sheet pinned up on the wall of Roger Toledo’s studio in Havana, Cuba. October 7, 2018.

Sierra: 22 days. Al Anochcer: 38 days. Nubes: 11 days. With a series of tally marks noted fastidiously on a sheet of paper tacked up on the wall in his former home and studio in Havana’s Vedado neighbourhood, artist Roger Toledo counts the number of days he has worked on each of the five paintings that comprise his Soy Cuba/I am Cuba series (2018-2019). Like the colorful marks that record his work days, the distinct pictorial units that comprise his paintings cumulatively compose sweepings views of historically-significant sites on the island. The works that make up the series traverse Cuba’s dynamic topographical landscape: in Aterrizando (Landing), nebulous forms congeal to create an expansive cloudscape. In Amanecer en el Pico Turquino (Sunrise at Pico Turquino), the sun rises over a sweeping view of the Sierra Maestra mountains as seen from the island’s highest peak. Viewers make their way through the grassy marshes of the Ciénaga de Zapata swamp in Cinéga de Zapata (Zapata Swamp), and waves come crashing towards a marina on the island’s north shore in Al Anochecer (At Dusk). The final work in the series, Hacia el Canto Del Veril (Toward’s Beril’s Edge), plunges viewers into the dark depths of the Straits of Florida along the northwestern coast of Cuba.

In three of the works that comprise Toledo’s series, Sunrise at Pico Turquino, Zapata Swamp, and At Dusk, sunlight acts as a marker of time that temporally situates depictions of three historically-significant sites within the time-span of a day: the morning sun graces the summit that was a key site during the Revolution, midday light exposes and heats up the swampy marshes of the site of the Batalla de Girón, known off-island as the battle of the Bay of Pigs, and twilight befalls an inky north shore marina, from which point thousands of Cubans have left their homeland on overcrowded boats and rafts. Although Toledo’s works that depict the three landscapes at different times of day may seem to chronologically position three distinct historical moments in Cuban history—the overthrow of Battista in 1959, the 1961 Batalla de Girón, and the waves of mass migration of the 1980s and 1990s—I suggest that his Soy Cuba series alternatively presents the extended temporality of revolutionary time in View from Pico Turquino, the intense “now” of the time of crisis in Zapata Swamp, the enduring present of the Special Period in At Dusk and the time of residence in Towards Beril’s Edge. Like the equalized units of color that comprise Toledo’s works, I suggest that the historical moments evoked in the paintings are positioned on an equal plane in the present and profoundly incite the engagement of viewers in the perception of time and history in the works.

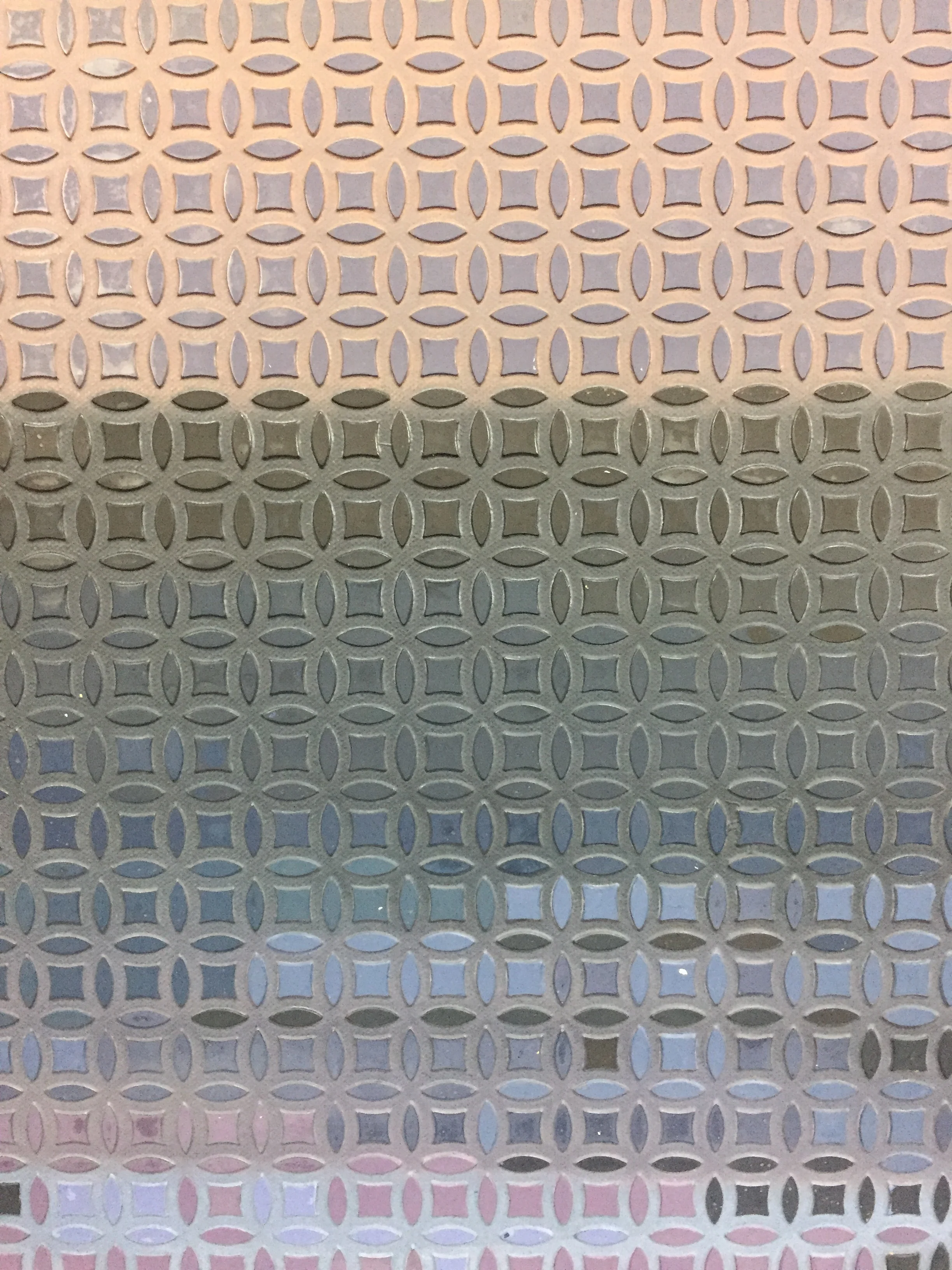

Roger Toledo, Al Anochecer (At Dusk) (detail), 2018, Acrylic on canvas, 78 3/4 x 118 inches (200 x 300 cm); Comprised by six panels of 39 3/8 x 39 3/8 inches (100 x 100 cm).

The series of tally marks pinned up on Toledo’s studio wall are pictorial records of the time of painting and the artist’s systematic division of his work hours into countable colorful streaks parallel his discreet painting technique.[1] Working primarily from photographs, Toledo begins by roughly sketching out his composition on six prepared canvases that fit together and are arranged to form a rectangle. Through the additive process of applying a mixture of acrylic paint thickened with modelling paste through the gridded pattern of metal radiator screens, he creates a haptic low-relief texture. Comprised of an all-over composition of repeating ovular and square shapes (which the artist refers to as “seeds” and “squares”), the geometric pattern allows Toledo to uniformly apply a single color to each one of the discreet pictorial units that compose the low-relief textures as each unit becomes a single, unblended shape of color. The artist works with adjacent and disjointed complementary and contrasting color values, and his paintings rely on viewer perception to knit together the various units of color that comprise his compositions are blended optically rather than on the artist’s palette.[2] While Toledo explores the interaction of singular unblended units of color in the relief patterns, colors merge in the backgrounds of his paintings. As such, despite the chromatic discreetness of the relief patterns that compose the foregrounds of Toledo’s works, the artist also relies on the viewer’s perception of minute and imperceptible tonal differences as colors blend and merge together in the backgrounds of his paintings. Toledo’s division of the picture plane into distinct color units presents time as a series of discreet events that can be counted, arranged, and re-arranged, and the artist’s sensitivity to minute chromatic variations allows viewers to draw together multiple temporalities in the present time of viewing.

The Extended Present Tense of the Revolution in Sunrise at Pico Turquino

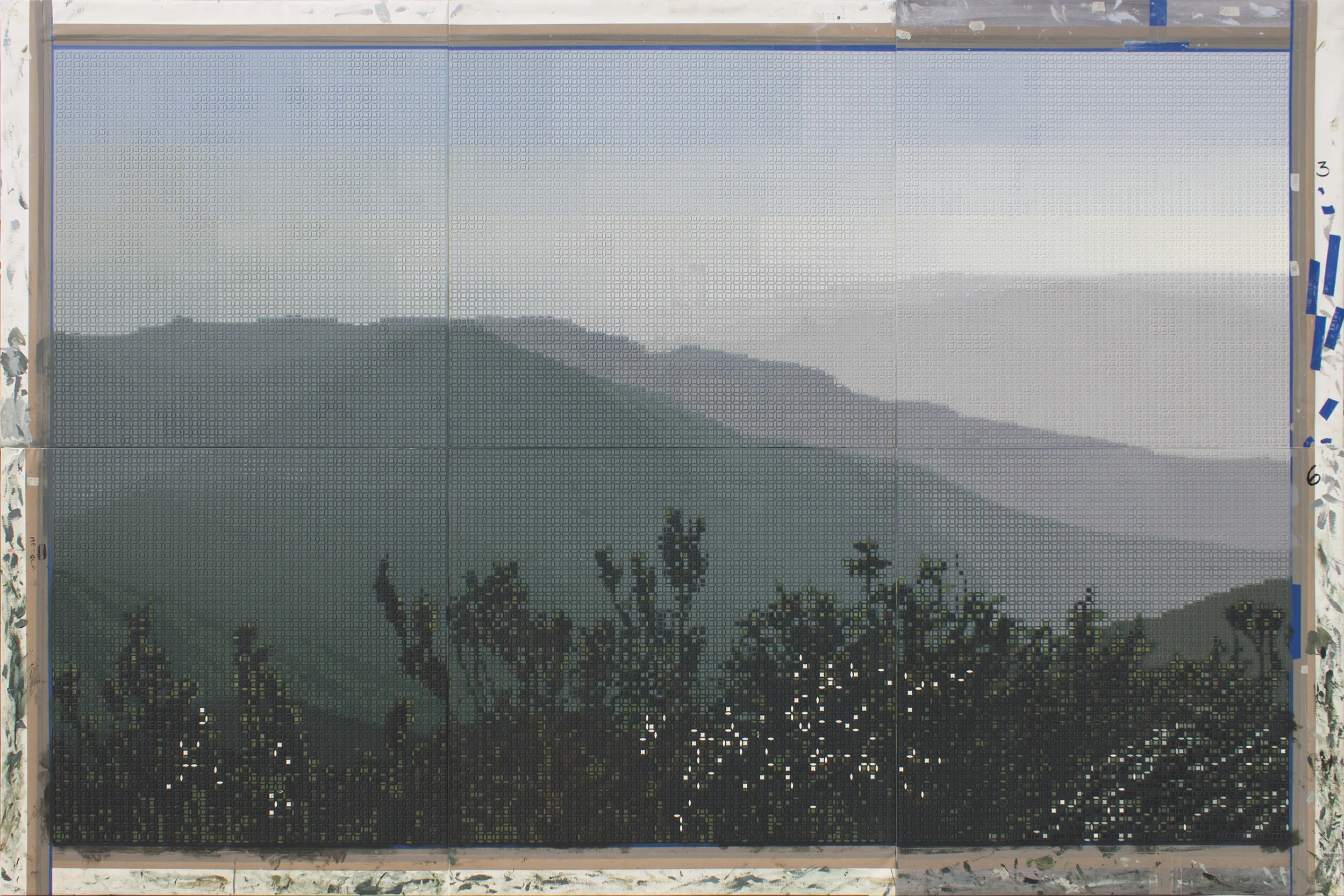

Roger Toledo, Amanecer en el Pico Turquino (Sunrise at Pico Turquino), 2018, Acrylic on canvas, 78 3/4 x 118 inches (200 x 300 cm); Comprised by six panels of 39 3/8 x 39 3/8 inches (100 x 100 cm).

A harmony of colors stratifies the sky as the sun rises over the Sierra Maestra mountains in Toledo’s Sunrise at Pico Turquino. Viewed from the island’s highest point at 1,974 m above sea level, the mountains emerge out of the distance in striking shades of dark turquoise and fade away as they receded into the background, their misty lilac hues fusing with the grey tones of the gradated sky.[3] Seen in the distance, they seem to approach towards viewers like ideas, histories, and stories not yet actualized, or recede into the background like forgotten dreams. Glimmers of sunlight tint the mountains as they rise towards the sky. The sun’s blazing light defines a new horizon and the shadowy mountains hold the full potential of everything that has yet to happen, everything that might be, and everything that might have been. “Sierra Maestra was this moment when all this new hope was starting for Cuba, this new day or new era,” explains Toledo.[4] Referring to the mountain range as emblematizing a moment in Cuban history that marked the beginning of a new epoch and demarcated the “then” from “now,” Toledo’s painting enfolds spatial and temporal registers as the layered hills of the Sierra Maestra come to embody the time of revolution.[5]

Extending from Cape Cruz to the Guantanamo river valley, the slopping valleys and soaring summits of the Sierra Maestra in southeastern Cuba retain the scars of a long history of revolutionary activity. An important site of insurgent activity during the Ten Year’s War (1868-1878), the Cuban War of Independence (1895-1898), and the Revolutionary War led by Fidel Castro, layers of patriotic struggle are stratified and preserved in the locale’s rich mountainous soil. In February 1957, Castro was interviewed and photographed by New York Times reporter Herbert Matthews amongst the trees and lofty peaks that served as a base for his group of insurgent guerilla fighters.[6] The resulting interview and images of the revolutionary leader on top of Pico Turquino graced the front pages of newspapers around the world, cementing Cuba’s highest mountain as a site quivering with revolutionary fervor in the cultural imagination. A few months later, the revolutionaries in the Sierra Maestra planted the Cuban flag atop Pico Turquino and proclaimed it Territorio Libre de Cuba.[7] As Cuban revolutionary and geographer Núñez Jiménez has stated, this declaration established the island’s highest mountains as the pinnacle of revolutionary activity: “After this proclamation by Fidel Castro and his men in olive green, Turquino became the capital of the Revolutionary Fatherland, the lighthouse that guided peasants, workers, and students towards the true path to National Liberation.”[8]

In Toledo’s painting, soft morning light washes over the grated layers of mountainous forms and past, present, and future are stratified within the image of the revolution like temporal sheets. The stratified layers propose a conception of the time of revolution as an extended time that carries the mark of the present rather than an endless chain of cause and effect where past and present are radically separated by a defining event. The temporal and spatial layering that is enacted pictorially in Toledo’s Sunrise at Pico Turquino evokes the artist’s process of building up a relief pattern on his canvases by applying layer upon layer of acrylic paint thickened with modeling paste to the parts of his canvases that are left uncovered by the metal sheets he lays on top of his paintings. Toledo’s additive process of constructing his images “from the ground up” recall the temporal thickness of revolutionary time. Indeed, layer after layer, the mountainous forms create a texture that simultaneously seems to advance towards the surface of the picture plane and then recede into the distance, enacting what João Felipe Gonçalves describes as the repetitive rather than teleological character of the “Revolution” in Cuba.[9] Exploring the temporality and historicity of revolution, Gonçalves posits the time of revolution as an extended heterogeneous time filled with advances and returns, invoking images of a revolution as a rotation on an axis rather than as a distinct rupture or change. As such, Toledo’s Sunrise at Pico Turquino proposes an encounter not only with the historical locale of the Sierra Maestra mountains but also with Cuba’s revolutionary past, present and future.

The Mixture of the Swamp in Zapata Swamp

The blazing light of the midday sun illuminates and exposes muddy greens and yellows in Toledo’s Zapata Swamp.

Roger Toledo, Cinéga de Zapata (Zapata Swamp), 2018, Acrylic on canvas, 78 3/4 x 118 inches (200 x 300 cm); Comprised by six panels of 39 3/8 x 39 3/8 inches (100 x 100 cm).

As one of the regions with the highest level of poverty on the island prior to the Revolution, the swampy marshes of Cuba’s southern shore were chosen as the site of the failed CIA-backed military invasion due to what was then perceived as the vulnerability and complacency of the area and its people.[10] On April 17, 1961, Brigade 2506, a group of US-trained Cuban exiles and American counterrevolutionaries, launched an invasion from the sands of the Playa Girón. As Mrs. Amparo, one of the four members of the Cuban Women’s Federation (FWC) from the Zapata swamp area describes in an interview, although the exiles expected to be greeted as liberators, the people of the swamp immediately recognized their presence as an invasion: “Well, we understood what was happening, seeing all those ships out there, and everything lit up and all that gunfire. You knew you were being attacked.”[11] Citing the dramatic improvement of living conditions on the island after the revolution, the members of the FWC describe Castro’s arrival to the Zapata swamp and their community members’ support of the Revolution: “No, it was easy; from the very triumph of the Revolution there was support for everything the Revolution did, because here the change was immediate and radical.”[12] Indeed, by the time the CIA-backed counterrevolutionaries invaded the area, a highway and new roads had been built, a handful of full-time doctors served the region, and several villages and schools had been established. The invaders were defeated by the Cuban military within three days.[13] The failed invasion of Playa Girón marks an important turning point in Cuban history, and the pressure of the moment is palpably felt in Toledo’s painting. The invasion of the area can be conceived of as a time of crisis, as a rupture between two states that revealed the uncertainty of the future. In Toledo’s painting, the feverish heat of the sun evokes the gravity of this decisive event in Cuban revolutionary history. Like a soupy concoction of various temporalities, the swampy marshes of the Cinéga de Zapata seem to contain the not-so-distant past, the intensity of the present, and near future and the buzzing inferno of the sun depicted in Toledo’s painting evokes the inchoate and confusing nature of transition. Conceived as the middle point in the series, Toledo’s Cinéga de Zapata marks the intensity of pivotal moments.

Enduring the Present in At Dusk

Roger Toledo, Al Anochecer (At Dusk), 2018, Acrylic on canvas, 78 3/4 x 118 inches (200 x 300 cm); Comprised by six panels of 39 3/8 x 39 3/8 inches (100 x 100 cm).

Rocked by the sea’s rolling waves, cloudy purples and inky blues enigmatically mingle with the last flickers of pale yellow sunlight peak through distant clouds in At Dusk. Presenting a view of the Florida Strait as seen from a north shore marina at Varadero, the setting sun illuminates the painting’s left side. Toledo’s painting faces North, where the shores of the United States loom and dip down into the Gulf of Mexico, towards the Caribbean island. Violet streaks cut across the sea at the bottom half of the canvas, veining the dark waters and breaking the ocean’s waves. A swell of water breaks and two parallel waves seem to echo each other as they come crashing towards the surface of the canvas. The setting sun pierces through a thick curtain of violet clouds, bringing both the threat of the encroaching night and the peaceful tranquility that comes with the end of the day, the last rays of revolutionary ideals or the end of an era. Simultaneously threatening and thick with the allure of unknown, dark horizons loom ahead.

In Toledo’s At Dusk, the shield of the night provides a calming shelter from the sun’s bright exposing rays, evoking conceptions of the darkness of twilight as a concealing shroud that enabled millions of economic migrants to travel to sanctuary. Wrapping themselves in the cover of darkness, millions of Cuban migrants have undertaken clandestine crossings of these dangerous waters in rustic vessels and makeshift rafts since the early 1960s. This wave of emigration peaked in the Spring of 1980, when around 125,000 Cubans migrated to the United States from the port of Mariel, about 20 miles west of Havana, during what is now known historically as the Mariel boatlift.[14] And in 1994, the sinking of a fleeing tugboat by Cuban patrol boats resulted in the death of at least 35 people and prompted a series of riots and another mass exodus of around 34,000 people. Furtive migration continued throughout the 1990s as material scarcity befell the island in the years immediately following the collapse of the Soviet Union during what became known as the “Período Especial” or “Special Period.” [15] Severe food shortages along with the establishment of drastic austerity measures and the imposition of a strict trade embargo by the United States (known commonly as bloqueo or “blockade”), led many Cubans to flee starvation.[16]

The quotidian struggle for survival during the Special Period has led to harsh demands on the present, requiring an intense commitment to the here and now. Indeed, anthropologist and historian Ariana Hernández-Reguant suggests that the hardships of the Special Period drastically sequestered and bracketed the historical epoch: “In the Special Period, there was a “before,” which was stable, perhaps purer in its altruism and high ideals, a “now,” which was confusing and unsettling, and a future that was, for many, another country. The experience was intense, yet the period was construed as a time of waiting: as an irresolute transition.”[17] According to Hernández-Reguant, the quotidian struggle of the 1990s marked the post-revolutionary period not as one of change and transformation but as a period of stagnation and waiting: a perpetual present during which the future only existed elsewhere, beyond the impasse of the sea. Indeed, anthropologist Amelia Rosenberg Weinreb also proposes that the beginning of the Special Period has come to drastically sequester the present from the past. She writes: “Cubans themselves now often use the start of the Special Period and the disturbing paradoxes it presented—no longer the revolution itself—as a historical “ground zero,” or reference point, of change, and there is a national discourse of antes de (before) the Special Period.”[18] According to Rosenberg Weinreb, a generalized past marks the long and undefined period that preceded the difficult present.[19]

In Toledo’s At Dusk, night falls over the north shore marina and the approaching darkness threatens to obscure the island, promising to reawaken it with the bright morning light of a new day. While the last glimmers of sunlight that illuminate the dark waters recall the shinning rays of the past (the way things were, the antes de), the darkness that befalls the marina and the perpetual rhythm of the waves that come crashing towards the north shore evoke the relentlessness and stagnation of what Hernández-Reguant and Rosenberg Weinreb have theorized as the perpetual present of the unending Special Period. However, by positioning the view facing the Florida Straits looking north, Toledo’s At Dusk addresses unseen shores: towards and beyond the deep waters that sequester the island. Beyond one’s field of vision, at the meeting of sky and sea in the upper third of the canvas, the horizon becomes heavy with the dangers of the ocean and the weighty, unknowable future.

The Perpetual Present of Residence Time in Towards Beril’s Edge

Roger Toledo, Hacia el Canto Del Beril (Toward’s Beril’s Edge), 2018, Acrylic on canvas, 78 3/4 x 118 inches (200 x 300 cm); Comprised by six panels of 39 3/8 x 39 3/8 inches (100 x 100 cm).

Serving both to connect and divide the island from its northern neighbor, the view across the Florida Strait to the north has been especially alluring to Cubans.[20] The waters that surround the island simultaneously encumber the possibility of escaping dire living conditions while providing Cubans with a potentially viable escape route to opportunity and prosperity. While Toledo’s At Dusk may evoke the hope and potential of the future, the work also conjures the risk and precariousness of clandestine migration and summons the ghosts of those who have perished while attempting the crossing, joining millions of other desperate migrants in the world’s largest graveyard. Although the United States government actively encouraged defection from Cuba during the Cold War (1947-1991), the stance towards Cuban asylum seekers changed drastically in 1994 when President Clinton announced that those who attempted to cross the Florida Straights to Miami would be interdicted at sea and taken to the US naval base in Guantánamo Bay, where they would be detained as “illegal refugees.”[21] Oral historian Elizabeth Campisi conducted interviews with twelve rafters who were detained during la crisis de los balseros (Cuban Rafter Crisis) of 1994-1996. She recounts: “At times my stomach sank while I heard stories of people being eaten by sharks, of the black waves surrounding rafts like walls at night, of people nearly drowning, or of others who had been burned with cigarettes by guards in Cuban prisons.”[22] The dangers involved in crossing the sea to Miami on rickety rafts was not unknown to those who attempted to flee lives made unlivable: “We would rather die together in the middle of the ocean than live in a country where there is no hope,” explained one of the rafters in an interview with Campisi.[23] Those who have died while attempting to cross the Florida Straits are not granted the peaceful rest that befalls life on earth but perpetually reside and cycle through the ocean’s waters. Scholar Christina Sharpe’s discussion of the “now” of Middle Passage residence time is a meaningful way to think through the temporality of those who did not reach foreign shores but perished at sea during migration. Pondering what has happened to the bodies of the enslaved Africans who were thrown overboard slave ships, Sharpe theorizes a residence time of the wake.[24] Evoking the 260 million years it takes for human blood to enter and leave the ocean, Sharpe conceptualizes residence time as a time in which “everything is now.” [25]

In Toledo’s Towards Beril’s Edge, signs of life flourish underwater as corals, marine plants, and grasses grow amongst the pebbles and rocks that cover the ocean floor. The underwater seascape pulls viewers down into watery depths, presenting a submerged view from the ocean floor. A bright blue saturates the image, its viscosity seething through and inundating the canvas. The unifying hue and foggy atmosphere unites the composition’s various elements—the rocks, plants, and corals of the underwater scene seem to blend together as the aquamarine shade permeates them. Despite Toledo’s methodical and precise manner of applying color to the small shapes that collectively comprise his paintings, the contours and edges of the various plants and rocks in Towards Beril’s Edge are left undefined and hazy, thereby evoking the mutual imbrication of all forms of life at the bottom of the sea. An enthusiastic diver himself, Toledo describes the serenity he experiences while underwater: “If you want to meditate and feel at peace, just go to the bottom of the ocean, sixty feet deep. It’s a strange relationship because you know you don’t belong there. . . but at the same time, there’s a very happy reconciliation with the environment, and every time I’m sleeping, I just think about being at the bottom of the ocean.”[26] What Toledo describes as the reconciliation he experiences with his immediate environment while submerged underwater evokes the possibility of joining those who have perished at sea, those whose blood and bodily tissues continually cycle through ocean waters according to the continual recycling of atoms in residence time.[27] The silence and stillness of underwater submersion may have enabled Toledo to attune himself to the temporalities of those who have perished at sea. Similarly, Towards Beril’s Edge plunges viewers into the depths of the ocean, thereby making possible new connections between the viewer’s own temporality and the perpetual “now” of residence time.

Rising over the Sierra Maestra mountains, looming over the Zapata swamp, and setting over a North Shore marina, the sun acts as a marker of the time of the day in three of the five paintings that comprise Toledo’s Soy Cuba series. In these paintings, three distinct historical moments—the Revolution of 1959, the 1961 Batalla de Girón, and the Special Period of the 1990s—are made to synchronize with uneasiness during the timespan of a day. Although the sequential nature of the paintings that comprise Toledo’s paintings may seem to evoke a conception of time and history as a chronological succession of distinct moments, I suggest that the series alternatively presents a type of non-teleological change that can only be perceived through the small incremental contingencies of the everyday. As Toledo affirms, it is through the viewers’ own temporal and spatial positionalities that various moments in Cuban history are evoked in the paintings and these encounters occur in the present time of viewing.[28]

[1] Working twelve hour days (often from 8:30 or 9:00 am to 8:00 pm) from Monday to Saturday, Toledo is methodical and systematic in keeping track of his working hours.

[2] Francesca Bolfo’s essay explores the artist’s engagement with color theory.

[3] The mountain’s name, Pico Turquino, is a reference to the peak’s blue hues.

[4] The artist in conversation with the curators on October 7, 2018 in Havana, Cuba.

[5] For a discussion of how the revolution radically separated the past from the present, see Louis A. Pérez, Jr., “Between the Old and New” in Cuba: Between Reform and Revolution (New York/Oxford: Oxford Univeristy Press), 2006.

[6] Peter Hulme, “Message in a Bottle: The Geography of the Cuban Revolutionary Struggle,” in Literature, Geography, Translation: Studies in World Writing, ed. Cecilia Alvstad, Stefan Helgesson, and David Watson (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011), 11-12.

[7] At Pico Turquino, artist Jilma Madera’s bronze bust of poet and revolutionary figure José Martí surveils the land from atop a rocky mound. Inscribed below the bust, Martí’s words are resonate throughout the mountains: [7]“Escasos, como los montes, son los hombres que saben mirar desde ellos, y sienten con entranas de nacion, o de humanidad.” (Scarce as the mountains are the men who can look down from them and feel their nation, or their humanity, move inside them.” Martí’s words were written in a letter to a friend before embarking on a journey to Cuba to join the war of independence and fight in the Battle of Dos Ríos where he died in 1895.

[8] Núñez Jiménez, Antonio. 1961. “En marcha con las brigadas estudiantiles hacia El Pico Turquino.” In ¡Patria o muerte…!, 7-24. Havana: INRA, 11 as quoted in Peter Hulme, “Message in a Bottle: The Geography of the Cuban Revolutionary Struggle,” in Literature, Geography, Translation: Studies in World Writing, ed. Cecilia Alvstad, Stefan Helgesson, and David Watson (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2011), 13.

[9] João Felipe Gonçalves, “Revolução, voltas e reveses. Temporalidade e poder em Cuba,” Revista Brasileira de Ciências Sociais (online), 2017, vol. 32, no. 93. http://dx.doi.org/10.17666/329305/2017.

[10] Margaret Randall, “Women in the Swamps” in Cuba Reader: History, Culture, Politics, Aviva Chomsky, Barry Carr, Pamela Maria Smorkaloff (North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2003), 363.

[11] Ibid., 367.

[12] Ibid., 365.

[13] Ibid., 364-369.

[14] Kenneth N. Nskoug, The U.S.-Cuba Migration Agreement: Resolving Mariel in Current Policy, no. 1050, March 1988, 1-6.

[15] Ariana Hernández-Reguant, Cuba in the Special Period: Culture and Ideology in the 1990s (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 1-2.

[16] Ibid., 8-9.

[17] Ibid., 2.

[18] Amelia Rosenberg Weinreb, Cuba in the Shadow of Change: Daily Life in the Twilight of the Revolution (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2009), 23.

[19] Amelia Rosenberg Weinreb, Cuba in the Shadow of Change: Daily Life in the Twilight of the Revolution (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2009), 23.

[20] Amelia Rosenberg Weinreb, Cuba in the Shadow of Change: Daily Life in the Twilight of the Revolution (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2009), 119.

[21] Elizabeth Campisi, Escape to Miami: An Oral History of the Cuban Rafter Crisis (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

[22] Ibid., 2.

[23] Ibid., 2.

[24] Christine Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 40-41.

[25] Ibid.

[26] The artist in conversation with the curators on October 7, 2018 in Havana, Cuba.

[27] Ibid.

[28] The artist in email correspondence with the curators, November 16, 2018.